Some bicycles don’t just take you places, they mean something. They carry within them stories, textures, intentions. When I came across Vetra Bikes, I immediately felt that sense of deeper connection: here was someone who wasn’t just welding frames, but crafting visual poems you can ride. In this interview, I had the pleasure of sitting down with the person behind it all: André Roboredo. Building, Art and Dreams.

Hi André, first of all, thanks so much for being here with me. For those who don’t know you yet, could you briefly introduce yourself? How old are you, where do you live now, and where are you originally from? What’s your background before getting to this point?

Hi Emanuelle, thank you for reaching out. Its a pleasure! I’m 35 years old from Portugal. And currently my workshop is located in Berlin Germany. I studied video art, visual communication and cinema in Porto Portugal which is my hometown. In school, I used to skip classes with my friends to ride locally built dirt jumps—it started seriously riding around 2005. I was really influenced by some of the first internet video releases from the New World Disorder series, and soon after I got hooked on trials riding, especially after watching Jeff Lenosky, Ryan Leech, and Cesar Cañas.

Many moons later, I started getting sponsorships, attending competitions, and doing demos around the country and filming video bike video parts for teams and brands. In 2009, I decided to shift my focus toward my studies—video art, visual communication, and cinema

"The bikes I build come out of shared stories, trips, textures, and friendships. They are not just made for riding, but for remembering, imagining, and exploring."

How did your passion for bicycles begin? Was it a sudden spark or a slow-burning journey shaped by people, travels, and experiences?

It started very early. My dad used to ride a GT Zaskar 26″ with a Manitou fork, Mavic ceramic wheels, and Magura HS-33s. When I was 10, he got me a 5-speed 20” MTB. From there, I dove into skateboarding, a bit of graffiti, small-scale airplane design and modeling, and eventually started doing trials and BMX.

I first got into handcrafts when a local model airplane veteran invited me to spend weekends at his house learning how to build planes. It was amazing—remote-controlled airplanes follow the same constraints as real ones, so I learned to work with wood, metal, fiberglass, soldering gas tanks, tuning engines, cutting patterns, and more. They have to be strong, light, and lean—there’s no shortcut in the process, they need to fly!

Fortunately I had a small basic workshop in the garage, and I was an unsettled kid, constantly riding—three hours a day, rain or shine. I kept breaking frames, so I started fixing them. By the time I was 17, I had built my first frame. Felt really good!

Through trials and bmx, I began traveling across the country, meeting new people, doing bike demos for kids, filming events and editing videos. The money I saved from demos went into interrail trips —we’d often skip country to country sleeping on trains or the streets. On one of those trips, in Croatia, I met two German skaters sleeping in the town square who invited me on a detour to their home city: Berlin. I said yes!

Years later, I moved to Berlin. At first, I worked as a 3D artist in media agencies, did bike deliveries, and spent time working at art studios. After a small burnout, and leaving cycling behind for a while, I felt the urge to reconnect with a different side of cycling. The idea of combining bikes and traveling felt like a dream. I started building 26” rat bikes from old MTB frames, and at the same time designed a modern 26” randonneuring frameset. I sent the design to my former sponsor, Marino Bikes, who built it for me.

That bike ended up taking me on a six-month tour through Peru and Bolivia, visiting Marino and crossing both countries.

When I came back from that trip I realized bikes held a deeper potential. They had followed me through different stages of life, shifting in meaning: from a tool of emancipation and physical exploration, to commuting and mechanical function/aesthetics. Over time, they shaped how I perceive the world and nature through my trips. I began to see the bicycle not just as merely a transportation vehicle, but as something that could carry context, emotion, and a sense of belonging.

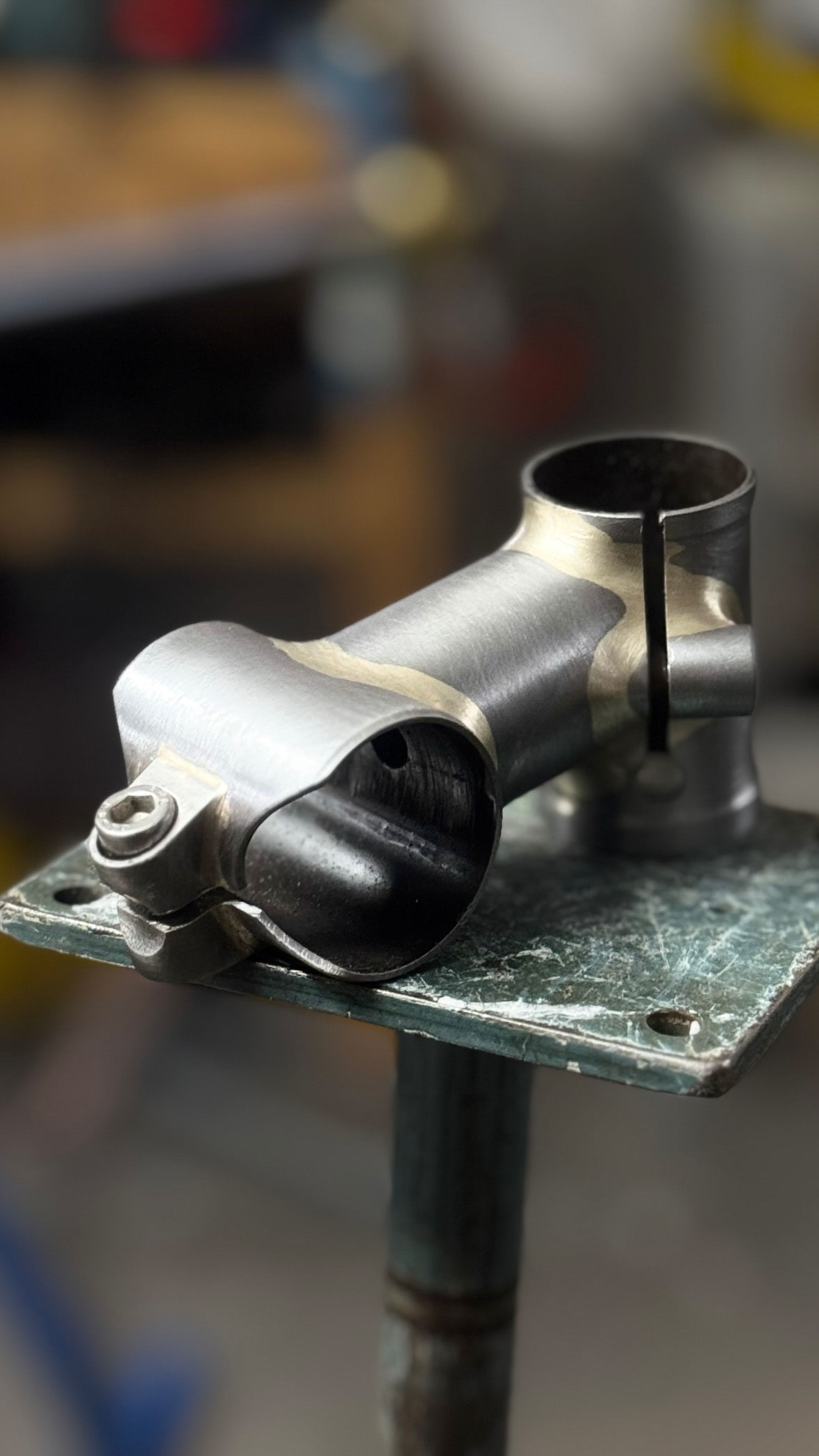

Soon enough after I made a frame with Robert at bigforest frameworks I realized I could actually make good frames with basic tooling so I fabricated a jig in my bedroom and slowly bought some basic essential tools and the journey started.

Berlin is a city I personally loved when I visited. What kind of relationship do you have with it? How much does it influence the way you think, create, and build?

In my opinion, Berlin is a very particular city in time and space, shaped deeply by its historical context, it resonated with me when I first visited. After the fall of the Wall, the combination of affordable housing and a relatively stable economy created a space where diversity and culture could really flourish. That mix led to a unique moment where you could balance work and personal life, while still developing your practice, doing research, going out, riding bikes, and being involved in music or club culture—without immediately getting trapped in housing schemes or underpaid full-time jobs straight out of university just to survive.

I think the history of the city, history and economy laid the foundation for that, but at its core, it’s the people—their resolve and their dreaming—that shape time and space. Berlin is very much that: a liminal place, full of chaos, where you can find threads of contrast and meaning—but where it’s also easy to get lost.

And as a cyclist, how is it to live in Berlin? Are there any destinations outside the city you like to reach to disconnect and find peace?

Berlin has an amazing ratio of nature to cityscape. There are plenty of parks, and if you’re looking to get off-grid, you can always find beautiful untouched pockets of nature in Brandenburg—just 30 minutes away by metro.

"A bicycle is more than a vehicle, it’s a vessel for memory, intention, and belonging. Each frame carries a conversation between material, experience, and the world around us."

Are there any routes or streets that you ride often and never get tired of? The kind of places that always feel new, no matter how well you know them?

I don’t find myself riding a lot in the city unless for commutes. If it’s sunny I love riding anywhere. I try to escape the city on the weekends and be in nature and do campouts with friends. In the city I have a couple of favorite technical trial rock sections in some parks that I like.

Let’s get back to your work. Vetra Bikes seems to reflect a broader idea of “making.” They feel like objects that tell stories, as if each piece was a chapter of a handwritten diary. Where does that attention come from? Is there an invisible thread that links art, design, craft, and culture in every frame?

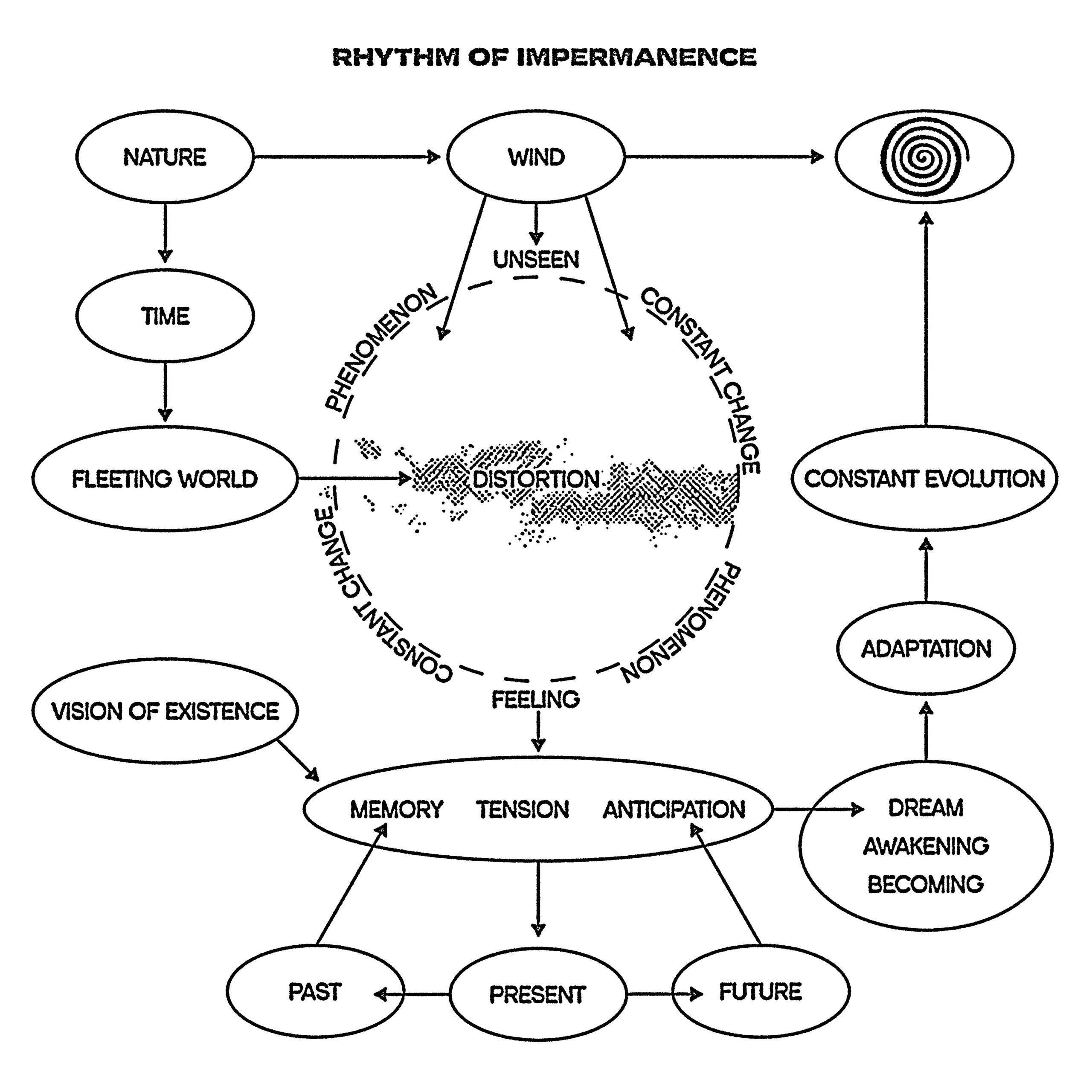

The practice of observation, contemplation, and research is something I carry into my spare time and often on bike trips. I often explore the etymology and phonetics of words, landscapes, as well as visual interpretation—images, artworks, memes, and so on. I’m interested in how things become what they are, and how they sit in time. Small symbolic traces often reveal historical contexts that shape how we perceive and understand things through a kind of collective memory.

I find myself drawn to concepts that link past and present memory. Some words, for example, feel uninhabited—rarely used or very specific in describing natural phenomena or scientific processes. They can feel like vacant vessels, open to new shapes and meanings. I like to speculate with clients, collaborators and friends around these kinds of concepts and around our experience of the world. Sometimes I find head spaces that feel open—fleeting but full of potential meaning. When you place those in relation to other words, images, or experiences, they can create new connections, new ways of seeing. Like meaning itself, which shifts through time.

This way of putting things tother probably comes from my background in image-making—working with collage, layering, moving parts around until a new composition emerges that can live on its own. Its a process. It’s similar with language: words are built from layers of meaning, consolidated into a form we use almost unconsciously. They’re strands of verbal and written memory that live in our collective understanding and get reinterpreted depending on who’s using them and how.

That’s what I try to do with Vetra bikes. It’s a process that mirrors consciousness, subjective artistry and nature: a continuous iteration of juxtaposing materials, feelings, concepts, metal, tubes, lines, and dots—until something emerges that expresses a particular relationship, experience, intentionality or sense of belonging. I try to bring this into my work with clients too. The only fixed binding guidelines is nature, and their own experience of cycling and the world.

You’re lucky to collaborate with two very special people: Christophe Synak and Rachel Walker. How did that collaboration begin and how does it work? Is it an ongoing dialogue or does everyone bring their world to the table unexpectedly?

Collaboration starts with mutual understanding, vision, and trust. When there’s trust, there’s mutual understanding—for the good and for the bad. I lived with Christophe for a year and with Rachel for five. I was brazing my first frames in my bedroom while Christophe brought me dinner, and we’d talk about life and possible takes on graphics—he does all the graphic design for Vetra now. Rachel saw the brand take shape up close too, and helped with organization, communication, and managing.

Having a small business in a manufacturing/creative field is, in many ways, an act of resistance in today’s market-driven world, and they both understood that from the start. They’ve been present in every stage of Vetra’s evolution, and we go on bike trips together when we can. The three of us come from backgrounds in art and culture, so the relationship has always been open and honest, full of shared references, ideas, and perspectives. Vetra wouldn’t be what it is without them—or without many others who helped with their input, advice, or just by being around.

The way we work is based on honesty and presence. We don’t take the process for granted, and that brings contrast and maybe clarity to whatever is at hand. That’s the language we try to build with each other. Coming back to your metaphor of “bringing to the table” — I feel like the table spins and flips in many directions. I think we try to understand and respond to that in our own ways, and when one of us has the task, we trust the outcome as part of a shared process. In the end, it becomes a language we speak together and somehow trust all its parts.

I recently saw your build based on a 90s Trek, pure beauty. Today, when a designer or framebuilder decides to go for 26″ wheels, do you think there’s still a meaningful reason behind that choice? Can it still make sense in a contemporary build, or is it mostly about nostalgia?

With bikes, nothing is set in stone. People don’t ride the same way, come back home on the same path or fall into the same pot holes. We’re all different—and once you go beyond just “rolling around,” it’s all about compromises.

26” bikes are nimble, compact, and fun compared to larger wheel sizes. Depending on tire width, they can even feel close to a 27.5”. The choice comes down to preference, budget, market availability, body size and intended use.

As a framebuilder—and more importantly, a trials/bmx rider—I see the value of 26” wheels in how they shape geometry. Factors for example like standover height, pedal stroke clearance, and chainstay length are naturally influenced. While 27.5” or 29” bikes can achieve similar ground clearance by adjusting bottom bracket drop, you tend to sit higher in relation to the wheel axles—more on top of the bike than inward between the wheels. That shifts your center of gravity in relation to the bicycles axles, which can feel less stable, but also allows for quicker input response and finer control, depending on the rider’s experience obviously. Personally I appreciate unstable bikes a lot!

Shorter chainstay configurations are also easier to achieve with 26” wheels too, making standing on the pedals body shifts to the rear wheel more direct and requiring less effort. The lower rotational mass adds to their agility too, and the smaller size gives your body more clearance when shifting weight over obstacles.

Beside some of these technical aspects in my view, 26” hits a sweet spot: budget-friendly, widely available on the second-hand market, and just plain fun, especially when rolling efficiency isn’t the main concern. Nostalgia definitely plays a role too; these old 26” bikes carry a wide variety of stories in our collective memory.

I’d absolutely consider building a 26” frame for a smaller rider with perhaps a taste for manuals, bunnyhops, jumps, and technical terrain—while still wanting some commuting ability. I have built one for myself, for fun with old parts I had in my workshop. It’s called the baby Chimera and its a ripper in many aspects.

Another point to all of this is also that sometimes, restoring or building a bike with all its quirks and features and understanding them deeply is far more fulfilling than just swiping a credit card at the bike shop. They are cheap and if you put work into research, learning mechanics and diving into the process it’s sometimes enough to make that bike feel like it’s an extension of your body. And that’s empowering!

As a graphic designer, I can’t help but notice the care you put into colors, textures, and even type. Your work reminds me of Dario Pegoretti or Antonio Colombo from Cinelli, who merged bikes, art, and culture so powerfully. Do you feel connected to that approach? And what does “making art” through a bicycle mean to you?

We all sit on the shoulders of giants. Pegoretti and Colombo are both references—not just in terms of aesthetics, but in how they approached bikes as vessels for culture, ideas, and emotion. Dario in particular had his way of sticking to the fundamentals—classic geometry, clean construction—but then adding these wild “modern art”, intentional touches that make every frame feel alive and human. And with Colombo, I love how he always had a curatorial eye, pulling in artists and letting the brand become a kind of collaborative space. That energy feels very alive too.

That’s something I really connect with. I often think about the risk of moving in multiple directions at once—how unpredictable that can be, but also how it mirrors the way people live and shape identity today. It applies to graphic design on Vetras too: the form might stay the same—the five Vetra letters—but the context is always shifting with its textures. New visions, new processes, new narratives. That’s what keeps it alive and interesting for me. The root meaning holds, but it’s constantly reinterpreted through lived experiences or people engaged into that process.

That’s also where aesthetics and materiality play a deeper role. Color, texture, surface—these are ways we connect, feel up close. There’s something primitive and instinctual about that. It becomes a primitive tool to shape narratives, to anchor feelings in form and expression.

Also, I have to say, I was genuinely amazed when I saw how you associated your recent handlebar design with the water spider. I thought, “That’s f**ing brilliant!”

How do you divide your time between planning and execution? Is there a particular moment in the process that you enjoy the most?

Thank you! Its funny actually, the Waterstrider bar came about when randomly I laid out three sets of the previously made Vetra Vulture bars on the workshop floor. I’ve been experimenting with flat bars, ergo horns, and other setups, and when I saw the tubes on the ground, it immediately reminded me of a water strider skimming across the workshop floor. I laughed and got to work, drawing on the angles and positioning from past bars experience. V1 rides great—still needs some minor tweaks and adjustments. Specific tooling to produce an actual model is in the works.

To answer your question, the moment I find more interesting is after spending a long time focusing on a project and finally putting it out. That’s when people begin to interpret it in their own way either with feedback from conversations, riding or just observing it. It’s like sending out a signal of experience and intent, and then watching it taking its shape and form. I learn a lot from people and it creates a reminder that we live in a perceived organized chaotic world full of interesting surprises. I appreciate that state of wonder of the unexpected.

Looking ahead: where is Vetra heading? What do you dream of for the future of the project?

Over the past year, I’ve been refining the framebuilding process to make it more efficient and focused. I’ve come to value more clarity over added complexity. Building bikes that are well-fitted, functional, and accessible within the customization realm. While I still appreciate intricate metalwork, I’ve grown less interested in creating a practice centered around showpieces that take weeks to complete. I don’t want our output to go exclusively to the highest bidder, nor do I want Vetra bikes to have exclusively the sole value of its practice translated into empty vessels featured on showrooms purely as purchasable objects of desire. They are important to show what you do and where you come from but that’s not all too it. I think in an initial stage it is good to push the craft limits but the reality is most people just need a good simple bike that fits them. Context and format is key. Sometimes the background is more important than the main focus. And for now I want to continue to work on accessibility and relationships. I’ll still make showbikes if the project feels right, or I have a crush on a particular design or a person’s vision but I’ve really come to enjoy teaching, hosting craft days in the workshop, and balancing work with passionate clients, friends, and like-minded people so I’ll probably be making some models in the future with some funky accents but keep it lean and purposeful.

To wrap things up, we’re currently organizing the third edition of the Framebuilding Festival in Argenta, Italy. It’s a small but truly passionate event. We’d be so happy to have you join us in one of the next editions, to share your vision, and maybe a few of your bikes too. What do you think?

That would be lovely! I’d definitely be up for visiting and meeting everyone. I’m planning a workshop move soon, so I’m not sure yet if the timing will overlap, but I’d really like to come by, maybe bring my bike, ride around, share some thoughts, have a good time with you all and try some tasty local food too.

Speaking with André was like riding along a quiet road that opens up unexpectedly to a view you didn’t see coming. His bikes aren’t just beautiful, they’re honest, intentional, and full of soul. In a world moving fast toward mass production, builders like him remind us that slowing down and making things with love still matters.